| Name: | Ansel Hurtis Clifton |

|---|---|

| Gender: | Male |

| Race: | White |

| Age: | 29 |

| Relationship to Draftee: | Self (Head) |

| Birth Date: | 7 Nov 1917 |

| Birth Place: | Appleby, Texas, USA |

| Residence Place: | Appleby, Nacogdoches, Texas, USA |

| Registration Date: | 11 Feb 1947 |

| Registration Place: | Appleby, Nacogdoches, Texas, USA |

| Employer: | Unemployed |

| Height: | 5 11 |

| Weight: | 147 |

| Complexion: | Ruddy |

| Hair Color: | Brown |

| Eye Color: | Gray |

| Next of Kin: | May Clifton |

U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946

| Name: | Ansel H Clifton |

|---|---|

| Race: | White |

| Marital Status: | Single, without dependents (Single) |

| Rank: | Private |

| Birth Year: | 1917 |

| Nativity State or Country: | Texas |

| Citizenship: | Citizen |

| Residence: | Nacogdoches, Texas |

| Education: | 3 years of high school |

| Civil Occupation: | Farm hands, general farms |

| Enlistment Date: | 23 Sep 1940 |

| Enlistment Place: | Lufkin, Texas |

| Service Number: | 18030825 |

| Branch: | Air Corps |

| Component: | Regular Army (including Officers, Nurses, Warrant Officers, and Enlisted Men) |

| Source: | Civil Life |

| Height: | 71 |

| Weight: | 141 |

They pulled us off into a rice paddy and began shaking us down. There [were] about a hundred of us so it took time to get to all of us. Everyone had pulled their pockets wrong side out and laid all their things out in front. They were taking jewelry and doing a lot of slapping. I laid out my New Testament. ... After the shakedown, the Japs took an officer and two enlisted men behind a rice shack and shot them. The men who had been next to them said they had Japanese souvenirs and money.

Word quickly spread among the prisoners to conceal or destroy any Japanese money or mementos, as their captors would assume it had been stolen from dead Japanese soldiers.

Prisoners started out from Mariveles on April 10, and Bagac on April 11, converging in Pilar, Bataan, and heading north to the San Fernando railhead. At the beginning, there were rare instances of kindness by Japanese officers and those Japanese soldiers who spoke English, such as the sharing of food and cigarettes and permitting personal possessions to be kept. This, however, was quickly followed by unrelenting brutality, theft, and even knocking men's teeth out for gold fillings, as the common Japanese soldier had also suffered in the battle for Bataan and had nothing but disgust and hatred for his "captives" (Japan did not recognize these people as POWs). The first atrocity—attributed to Colonel Masanobu Tsuji—occurred when approximately 350 to 400 Filipino officers and NCOs under his supervision were summarily executed in the Pantingan River massacre after they had surrendered. Tsuji—acting against General Homma's wishes that the prisoners be transferred peacefully—had issued clandestine orders to Japanese officers to summarily execute all American "captives". Although some Japanese officers ignored the orders, others were receptive to the idea of murdering POWs.

During the march, prisoners received little food or water, and many died. They were subjected to severe physical abuse, including beatings and torture. On the march, the "sun treatment" was a common form of torture. Prisoners were forced to sit in sweltering direct sunlight without helmets or other head coverings. Anyone who asked for water was shot dead. Some men were told to strip naked or sit within sight of fresh, cool water. Trucks drove over some of those who fell or succumbed to fatigue, and "cleanup crews" put to death those too weak to continue, though some trucks picked up some of those too fatigued to go on. Some marchers were randomly stabbed with bayonets or beaten.

Once the surviving prisoners arrived in Balanga, the overcrowded conditions and poor hygiene caused dysentery and other diseases to spread rapidly. The Japanese did not provide the prisoners with medical care, so U.S. medical personnel tended to the sick and wounded with few or no supplies. Upon arrival at the San Fernando railhead, prisoners were stuffed into sweltering, brutally hot metal box cars for the one-hour trip to Capas, in 43 °C (110 °F) heat. At least 100 prisoners were pushed into each of the unventilated boxcars. The trains had no sanitation facilities, and disease continued to take a heavy toll on the prisoners. According to Staff Sergeant Alf Larson:

The train consisted of six or seven World War I-era boxcars. ... They packed us in the cars like sardines, so tight you couldn't sit down. Then they shut the door. If you passed out, you couldn't fall down. If someone had to go to the toilet, you went right there where you were. It was close to summer and the weather was hot and humid, hotter than Billy Blazes! We were on the train from early morning to late afternoon without getting out. People died in the railroad cars.

Upon arrival at the Capas train station, they were forced to walk the final 9 miles (14 km) to Camp O'Donnell. Even after arriving at Camp O'Donnell, the survivors of the march continued to die at rates of up to several hundred per day, which amounted to a death toll of as many as 20,000 Americans and Filipinos. Most of the dead were buried in mass graves that the Japanese had dug behind the barbed wire surrounding the compound. Of the estimated 80,000 POWs at the march, only 54,000 made it to Camp O'Donnell.

The total distance of the march from Mariveles to San Fernando and from Capas to Camp O'Donnell (which ultimately became the U.S. Naval Radio Transmitter Facility in Capas, Tarlac; 1962–1989) is variously reported by differing sources as between 60 and 69.6 miles (96.6 and 112.0 km). The Death March was later judged by an Allied military commission to be a Japanese war crime.

Camp O'Donnell was the destination of the Filipino and American soldiers who surrendered after the Battle of Bataan on April 9, 1942.

The first Filipino and American POWS arrived at Camp O'Donnell on April 11, 1942 and the last on June 4, 1942. The Filipinos and Americans were housed in separate sections of the camp. There was a constant movement in and out of the camp as the Japanese transferred prisoners to other locations on work details. In June, most of the American POWs were sent to other POW camps or to work sites scattered around the country and ultimately to Japan and other countries. From September 1942 to January 1943, Japan paroled the Filipino POWs. They signed an oath not to become guerrillas, and the mayors of their home towns were made responsible for their conduct as parolees. Japan closed Camp O'Donnell as a POW camp on January 20, 1943.

|

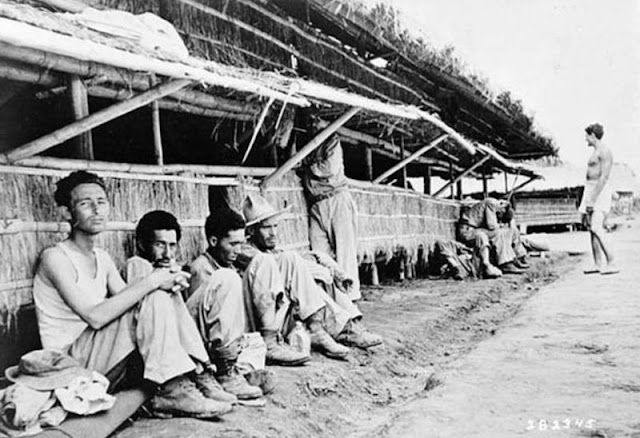

| Prisoners sit next to a thatched hut in the early days of the war at Camp O'Donnell. This was taken in May of 1942, one month after the camp was opened and the fall of the Philippines. |

The POWs at Camp O'Donnell died in large numbers due to a number of reasons. Japanese soldiers rarely surrendered and held those who did in contempt. The Japanese soldier was the product of a brutal military system in which physical punishment was common and they treated the POWs accordingly. Moreover, the Filipino and American soldiers arriving at Camp O'Donnell were in poor physical condition, having survived on short rations for several months. Many were suffering from malaria and other diseases. The Japanese had made little provision for the treatment of prisoners and were surprised at the large number they captured. They had believed the force opposing them in Bataan was much smaller and that the prisoners would number only about 10,000 rather than the 70,000 or more they actually captured. The Japanese were unprepared to provide the POWs with adequate food, shelter, and medical treatment. Japanese military leadership was inattentive to the POWs, preoccupied with completing their conquest of the Philippines. Moreover, the Japanese declined to treat the POWs in accordance with the Geneva Convention of 1929, which Japan had signed but had not ratified.

|

| The remains of Camp O'Donnell, Luzon, Philippines. February 14, 1945. |

Conditions at Camp O'Donnell were primitive. The POWs lived in bamboo huts, sleeping on the bamboo floor often without any covering. There was no plumbing; water was scarce. Weakened by malaria, dysentery was rampant. Medicine was in short supply. Food consisted of rice and vegetable soup, occasionally with shreds of water buffalo meat. The diet provided about 1,500 calories daily and was deficient in protein and vitamins. Vitamin deficiency illnesses such as beri-beri and pelagra developed among many. The Japanese refused most offers of assistance for the POWs, including from the Philippine Red Cross.

As American forces continued to approach Luzon, the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters ordered that all able-bodied POWs be transported to Japan. From the Cabanatuan camp, over 1,600 soldiers were removed in October 1944, leaving over 500 sick, weak, or disabled POWs.

A hell ship is a ship with extremely inhumane living conditions or with a reputation for cruelty among the crew. It now generally refers to the ships used by the Imperial Japanese Navy and Imperial Japanese Army to transport Allied prisoners of war (POWs) and romushas (Asian forced slave laborers) out of the Dutch East Indies, the Philippines, Hong Kong and Singapore in World War II. These POWs were taken to the Japanese Islands, Formosa, Manchukuo, Korea, the Moluccas, Sumatra, Burma, or Siam to be used as forced labor.

INRIN TEMPORARY CAMP

Camp Opened: 11/08/44 - Camp Closed: 01/16/45

Following the harrowing voyage of the hellship Hokusen Maru to Taiwan from October 1st to November 8th 1944, a group of 336 American and 46 British POWs were sent to a camp that was set up in a school - also in the town of Inrin (Yuanlin). This camp was close to the main Inrin Camp - in fact the two camps were less than a kilometre apart. When the men first arrived in the camp nothing was set up or ready for them, so some of the POWs from the main camp came over and helped them set up their kitchen and prepared their first meals until the camp got better established.

The men, having endured such an ordeal on the hellship, were not required to do any real hard work as such. They were engaged mostly in keeping the camp in order and farming on the hillsides above the camp. There they grew vegetables to supplement their diet and as a result many of the men recovered and became more fit again.There were no POW deaths in this camp.

In mid-January 1945 the camp was emptied and the men were sent to either Takao or Keelung and put on other ships for transport to Japan. There they finished the war in a number of camps - some on Kyushu and some in the Sendai area in the north of Japan. They were subsequently evacuated by Allied forces after the Japanese surrendered.

CLIPPED FROM

The Daily Notes

Canonsburg, Pennsylvania

16 Jan 1947, Thu • Page 3CLIPPED FROM

Tyler Morning Telegraph

Tyler, Texas

13 Oct 1999, Wed • Page 16

Ansel H Clifton

| BIRTH | |

|---|---|

| DEATH | 12 Oct 1999 (aged 81) |

| BURIAL | Nacogdoches, Nacogdoches County, Texas, USA |

No comments:

Post a Comment